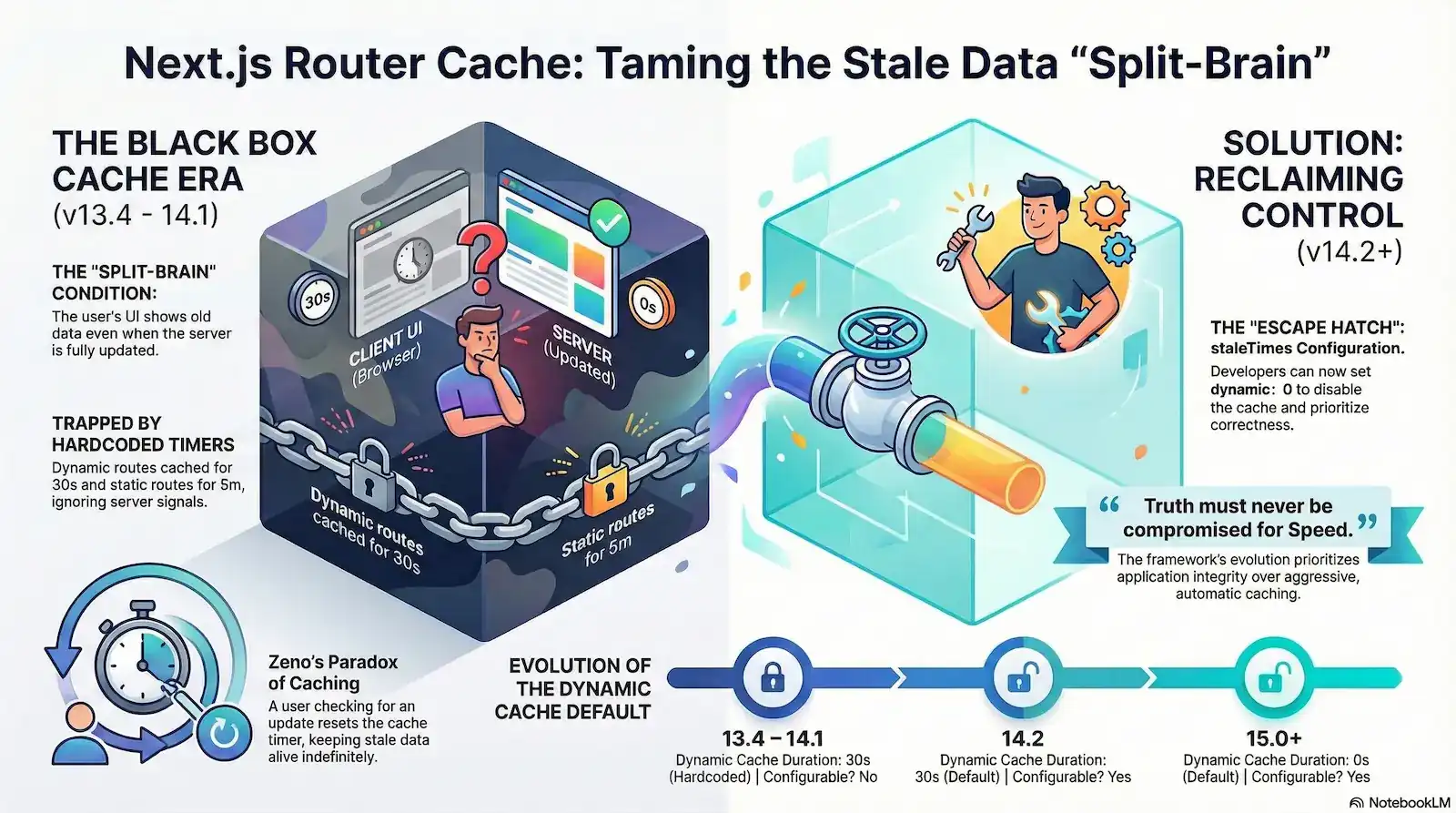

The Next.js Client-Side Router Cache is an in-memory repository for React Server Component (RSC) payloads that exists entirely within browser heap memory. Unlike the HTTP Disk Cache, it is governed by hardcoded client-side heuristics (30 seconds for dynamic routes, 5 minutes for static) rather than standard

Cache-Control headers. Its primary purpose is to enable “instant” transitions and preserve UI state like scroll position during navigation.

Your server logs show a 200 OK. Your database confirms the update. You have even set export const dynamic = 'force-dynamic' to ensure every request is fresh. Yet, the user’s browser remains stubbornly frozen in time, displaying a record that was deleted minutes ago. This isn’t a simple race condition; it’s a fundamental architectural “Split-Brain” condition where the server’s truth and the client’s reality are completely decoupled.

Technical Definition: Borrowing from distributed systems theory, this describes a state of structural incoherence where the Server (Node A) and the Client UI (Node B) diverge. Communication has effectively “partitioned” because the Client-Side Router Cache is operating independently of the server’s data reality.

Forensic Marker: This occurs when the server has successfully regenerated a page (ISR hit), but the browser’s internal heap memory remains “locked” to a previous version. Like a split-brain in a database cluster, both “nodes” believe they have the correct version of the truth, leading to a “ghost” state for the user.

The culprit is the Next.js Client-Side Router Cache—an “un-fakeable” failure point that operates as a total “black box,” often ignoring server signals and standard Cache-Control headers entirely. For senior engineers, this behavior feels less like a performance optimization and more like technical gaslighting. You see the fresh renders hitting your server logs in real-time, but the browser continues to serve stale data from a hidden internal memory.

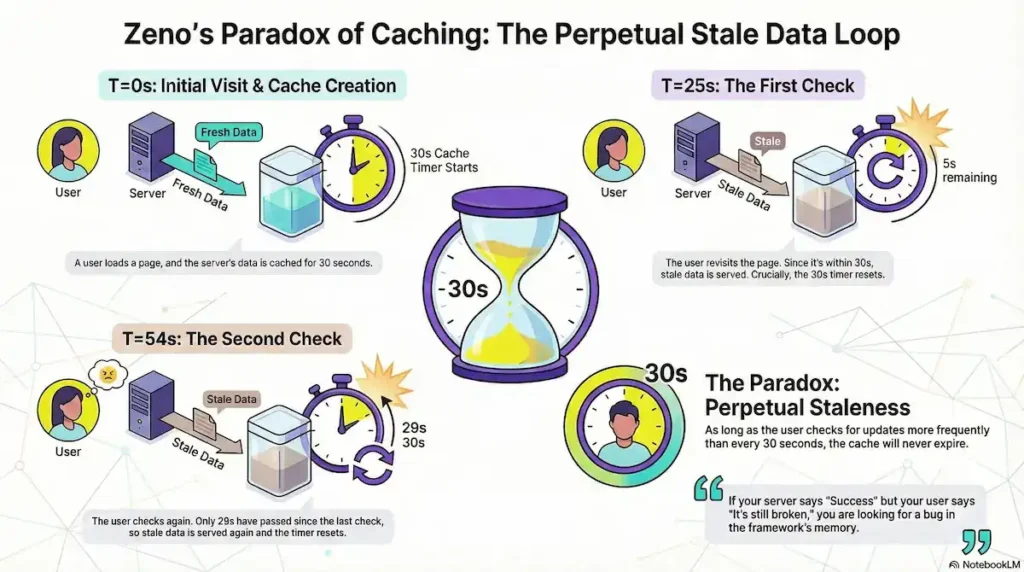

This architectural choice creates what we call the “Zeno’s Paradox of Caching”. In versions 13.4 through 14.1, the very act of a user checking for an update actually prevents that update from appearing. Because navigating to a route resets the internal stale-time counter, frequent user interaction can effectively keep stale data alive indefinitely. The harder the user looks for the “truth” by clicking through the navigation, the further away it stays.

We are moving past the era of being trapped by these rigid, automatic heuristics. This analysis reconstructs the forensic failure points of the early App Router iterations and identifies the specific “escape hatches” introduced in Next.js 14.2 and 15. We will show you how to finally bridge the gap between your server-side logic and the client-side UI, ending the era of “ghost” states and unpredictable stale data.

The “Black Box” Problem: Why Your Next.js App Shows Stale Data

Technical Definition: A system whose internal workings are opaque to the observer, requiring “un-fakeable” evidence to reverse-engineer its behavior.

In Next.js Context: The Client-Side Router Cache functions as a “Black Box” because it operates entirely within the browser’s heap memory, bypassing the standard Network Layer. This makes its behavior invisible to both server-side monitoring and standard browser DevTools. Prior to version 14.2, its hardcoded heuristics (30s/5m timers) provided no Observability API, effectively locking developers out of their own application’s state management and forcing a reliance on “blind” workarounds.

To solve the stale data problem, we must first define what the Client-Side Router Cache actually is. Unlike the Browser HTTP Disk Cache—which stores static assets like CSS and JS—or the Server-side Full Route Cache, the Router Cache is a distinct, in-memory repository for React Server Component (RSC) payloads stored directly in the browser’s heap memory.

This cache does not store HTML. Instead, it stores a serialized JSON representation of your components. This payload contains the raw data, the component tree structure, and the specific instructions React needs to reconcile the Virtual DOM without a full page reload. When a user clicks a <Link> component, the Next.js router intercepts the navigation intent. Instead of executing a standard document request that would hit your server, it checks this local memory store first.

This “interception layer” is why your server logs often remain silent when a user navigates between pages. Because the request never leaves the browser, the server never has a chance to provide fresh data. This creates an “un-debuggable gap” for engineers: you are looking at your backend for answers to a problem that is happening entirely within the client’s heap memory.

Even more confounding is the cache’s header ignorance. Unlike standard fetch requests that respect the web’s caching contracts, this router cache frequently ignores Cache-Control: no-store or no-cache headers in favor of its own internal JavaScript heuristics. Once an RSC payload is acquired, it operates independently of the server’s state.

The result is a persistent “Split-Brain” condition where your application’s state is fractured across three disconnected layers:

- The Server Truth: Your database and server components have successfully regenerated a fresh state (via ISR or a dynamic render).

- The Transmission Layer: The network remains idle because the router has bypassed the need for a new request.

- The Local Memory Layer: The client-side router serves a “past state” from its internal cache node, presenting the user with a “ghost” of the application’s previous data.

This decoupling means that even if you confirm a fresh hit on the server, the client UI remains trapped in the “Black Box,” oblivious to any updates that occurred after the initial session load.

Decoding the Heuristic Matrix: The 30s and 5m “Hardcoded” Era

During the Next.js v13.4–14.1 era, developers were subjected to a rigid, opaque caching architecture. The framework utilized hardcoded durations for the Client-Side Router Cache that were entirely inaccessible to configuration. These “hidden rules” often contradicted standard web expectations, leading to the friction many engineering teams experienced when trying to ship dynamic applications.

To understand the logic of this era, you must view the application through the lens of these two primary temporal buckets.

Next.js v13.4–14.1 Router Cache Heuristics

| Segment Type | Trigger Condition | Hardcoded Duration | Observed Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Routes | Use of cookies() , headers() , or no-store | 30 Seconds | Cache persists; ignores server-side dynamic flags for 30s. |

| Static Routes | Statically generated or prefetch={true} | 5 Minutes | Aggressive reuse; overrides ISR or server revalidation for 300s. |

| Back/Forward | Browser history navigation | Indefinite | UI is restored from session memory to preserve scroll/layout. |

The Logic Matrix Breakdown:

- Dynamic Route Constraints: Even if you explicitly declared

export const dynamic = 'force-dynamic', the router would still bucket the page into the 30-second window. The intent was to prevent “flashing” during rapid navigation, but the result was a 30-second blackout where fresh data was effectively blocked from the UI. - Static Route Persistence: For routes that Next.js deemed “static,” the framework applied a heavy-handed 5-minute (300s) cache. This was particularly problematic for apps using Incremental Static Regeneration (ISR). While your server might have regenerated the page in the background after 60 seconds, the client-side router would continue to serve the 5-minute-old “ghost” version stored in the browser’s heap memory.

- The Navigation Stability Intent: The primary architectural goal for these values was to emulate “bfcache” (Back/Forward Cache) behavior. By keeping the cache alive indefinitely for history navigation, Next.js ensured that clicking “Back” was instantaneous and preserved the user’s scroll position and layout state.

The friction arose because the documentation during this period framed these hardcoded durations as “optimizations”. However, for developers building real-time dashboards or e-commerce platforms, these optimizations functioned as architectural constraints. Without the ability to tune these timers, teams were forced into “active subversion”—using hacks like manual router.refresh() calls or appending random query strings to URLs—just to bypass the framework’s internal logic and force a fresh data fetch.

Zeno’s Paradox: The “Reset on Navigation” Bug Explained

The most insidious aspect of the Next.js v13.4–14.1 caching behavior wasn’t just that the cache existed—it was how the framework determined when that cache was “old.” This created a phenomenon we call “Zeno’s Paradox of Caching.” In this architectural flaw, the very act of a user checking for an update effectively ensured they would never receive it.

Philosophical Origin: Zeno’s paradoxes are a set of philosophical problems generally thought to have been devised by Zeno of Elea to support Parmenides’ doctrine that “all is one” and that, contrary to the evidence of our senses, motion is nothing but an illusion.

Technical Application: In the Next.js 13.4–14.0 runtime, we see a digital version of the “Achilles and the Tortoise” race. Achilles (the Cache Expiration) can never actually reach the Tortoise (the 30-second TTL) because every time the user interacts with the page, the “finish line” for expiration is moved further down the road. In this environment, interaction is the enemy of accuracy.

In a standard TTL (Time-To-Live) implementation, a 30-second cache expires 30 seconds after the initial fetch, regardless of what the user does. However, forensic analysis of early App Router versions (13.4–14.0) revealed that the 30-second timer for dynamic segments was not a fixed expiration date. Instead, the system appeared to reset the “last active” timestamp every time the user navigated back to that cached segment.

To understand how this traps a user in a “ghost” state, consider this reconstructed timeline of a user waiting for a database update:

- T=0s (Initial Visit): The user navigates to

/dashboard. The router fetches the RSC payload from the server and creates a cache entry. - T=25s (The First Check): The user, anxious for an update, clicks a link back to

/dashboard. The system sees that only 25 seconds have elapsed—well within the 30-second hardcoded window. Action: It serves the T=0 payload from memory and, crucially, updates the “last active” timestamp to T=25s. - T=54s (The Second Check): The user clicks again. The system compares the current time (54s) to the last active time (25s). Since only 29 seconds have elapsed since the last interaction, the cache is still considered “fresh”. Action: The user sees the stale data again, and the timer resets once more to T=54s.

The Paradox Outcome: Perpetual Staleness

If your server says ‘Success’ but your user says ‘It’s still broken,’ you aren’t looking for a bug in your code. You are looking for a bug in the framework’s memory.

As long as a user interacts with a route more frequently than the 30-second threshold, the cache never expires. This creates a deterministic failure: the more engaged or “impatient” the user is, the more likely they are to be served stale data indefinitely.

The operational impact is devastating for applications requiring real-time status updates. A user waiting for a transaction to move from “Pending” to “Approved” will naturally refresh or re-navigate to the page. If they do this every 20 seconds, they unknowingly keep the “Pending” state alive in their browser’s heap memory, even if the server processed the “Approved” state minutes ago. This isn’t just a technical bug; it is a psychological failure point that leads users to believe the entire application is broken or “stuck,” when in reality, they are simply victims of an aggressive, self-perpetuating cache logic.

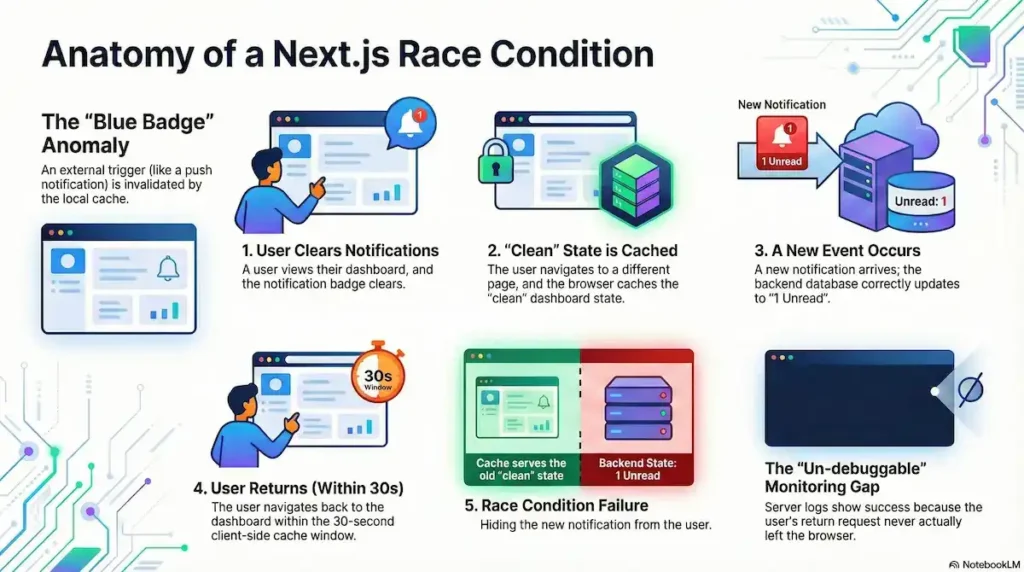

The Notification Race Condition: When “Blue Badges” Fail

The “Notification Race Condition” is the most frequent source of “it works on my machine” tickets in the Next.js App Router era. It represents a fundamental breakdown between real-time data expectations and the framework’s aggressive client-side persistence. For engineers, this scenario is a nightmare to debug because, on the surface, every system is performing exactly as designed.

The Anatomy of a Silent Failure

Technical Definition: A specific class of state-synchronization failure where an external state trigger (such as a WebSocket push or a notification badge) is invalidated by a local, interaction-based cache timer.

Forensic Marker: This occurs when a UI element correctly signals that new data exists (the “Blue Badge”), but upon navigation, the Client-Side Router intercepts the request and serves a “clean” stale version from its internal heap. This creates a high-friction UX where the application’s “Awareness” (Notifications) and its “Reality” (The Page Content) are fundamentally out of sync due to the 30-second latch of the framework’s internal heuristics.

Consider the “Blue Badge” anomaly—a sequence where a user’s interaction and the router’s cache logic collide to create a broken UX:

- The Interaction: A user sees a notification badge, clicks into their dashboard, and the badge clears. They have now viewed their notifications, and the dashboard is “clean.”

- The Exit: The user navigates to a different page (e.g., /settings). At this moment, the browser stores the “clean” dashboard state in its heap memory.

- The New Event: Five seconds later, a fresh notification arrives. Your backend processes the event and correctly updates the database to “1 Unread”.

- The Return: Within that same 30-second window, the user navigates back to the dashboard to check the new notification.

This is where the race condition triggers a failure. Because the user returned within the silent 30-second window, the Client-Side Router Cache intercepts the request.

The router identifies a “valid” cache entry (which is technically only a few seconds old from its perspective) and serves the old dashboard state. The result? The user sees a cleared badge despite knowing they have a new message.

The “Un-debuggable” Monitoring Gap

This creates a massive visibility gap for engineering teams. When the user submits a bug report, the developer checks the server logs. They see a successful render for “1 Unread”. From the server’s perspective, the “truth” was sent.

However, the server logs are completely empty for the user’s return visit because the request never actually left the browser. This is a “silent failure” that standard monitoring tools like Sentry or Datadog cannot capture without custom client-side instrumentation. The framework’s documentation during this period failed to warn that these interaction-based race conditions were not just possible, but inevitable for any app with high-frequency state changes.

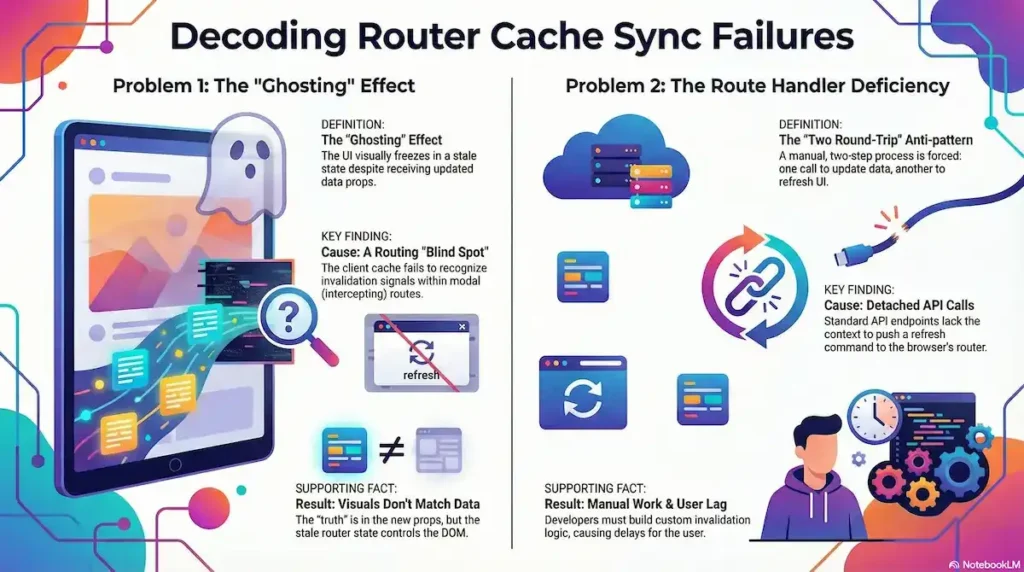

Invalidation Blind Spots: Parallel Routes and “Two Round-Trip” API Calls

Even when developers attempt to play by the rules, the Next.js invalidation ecosystem often fails in non-deterministic ways. The primary reason is that standard invalidation signals like revalidatePath and revalidateTag were designed for the server-side Full Route Cache, but they frequently fail to penetrate the Client-Side Router Cache, especially in complex layouts.

`revalidateTag` updates the client UI instantly

Fact: It is a server-side-only invalidation that requires a client-side trigger

Parallel Routes: The “Intercepted” Blind Spot

The most documented failure occurs within Parallel and Intercepting Routes. In the Lab, we classify this as the ‘Intercepted Blind Spot.’ While not yet documented as a canonical fault pattern by Vercel, forensic evidence in GitHub Issue #54173 reveals a structural ‘partition’ where revalidatePath signals fail to penetrate the client-side reconciliation logic of parallel segments

- The Problem: A developer triggers an action within a modal (Intercepted Route) that should update the background page (Parallel Route).

- The Cause: While

revalidatePathsuccessfully clears the server-side cache, the Client Router Cache often fails to recognize the invalidation signal for the specific segment currently “intercepting” the route. - The Effect (Ghosting): This leads to the “Ghosting” phenomenon. Forensic traces show that the client component may even receive new props in the logs, but because the React tree reconciliation logic is tied to the stale router segment, the visual UI remains frozen. The “truth” is in the props, but the “stale state” is in the DOM.

Technical Definition: A state of UI-reconciliation failure where a React component’s props are successfully updated (verified via logs or DevTools), but the visual DOM remains “frozen” in a stale state because the Client-Side Router has failed to reconcile a specific intercepted or parallel segment.

Forensic Marker: This is identified by a “Truth-UI Gap.” Using useEffect or console logs, the developer can see the new data arriving in the component’s props, yet the browser screen refuses to re-render. This occurs primarily in Parallel Routes, where the framework’s internal “segment tracking” loses sync with the server’s revalidation signal.

The Route Handler Deficiency

A critical architectural disconnect exists between Server Actions and standard Route Handlers (API endpoints). While Server Actions have a “privileged” connection to the router, standard API calls do not.

- The Problem: Calling

revalidateTagorrevalidatePathinside a standardGETorPOSTRoute Handler successfully purges the server’s data cache but has zero effect on the user’s current browser session. - The Cause: Unlike Server Actions—which bundle an instruction to the router to refresh the current page—standard

fetchcalls to API endpoints are detached from the router’s context. They cannot “push” an invalidation signal to the browser’s heap memory. - The Effect: This creates the “Two Round-Trip” Anti-pattern. Developers cannot simply call an API; they are forced into a manual choreography: first, executing

await fetch('/api/update')to mutate the data, and second, manually callingrouter.refresh()to force the router to purge its internal cache.

Technical Definition: A forced manual choreography necessitated by Context-Blind APIs (standard Route Handlers), where a developer must execute a data mutation followed by a separate, manual client-side cache purge because the initial request lacks the privilege to invalidate the browser’s router memory.

Forensic Marker: This is identified by two distinct, sequential network entries for a single user action:

- Request A (The Mutation): A standard

fetchorXHRto an API endpoint that updates the server-side state. - Request B (The Sync): A subsequent RSC payload request triggered by

router.refresh()to force the UI to recognize the change.

In the Lab, we classify this as an anti-pattern because it doubles the network overhead and shifts the burden of State Orchestration from the framework back to the engineer.

This reliance on manual router.refresh() calls is a significant source of friction. It forces engineers to build “custom invalidation managers” just to ensure the UI matches the database—a task that a modern framework’s router is theoretically supposed to handle automatically. By the time the developer triggers the second round-trip, the user has already experienced a multi-second delay where the application appeared unresponsive or stale.

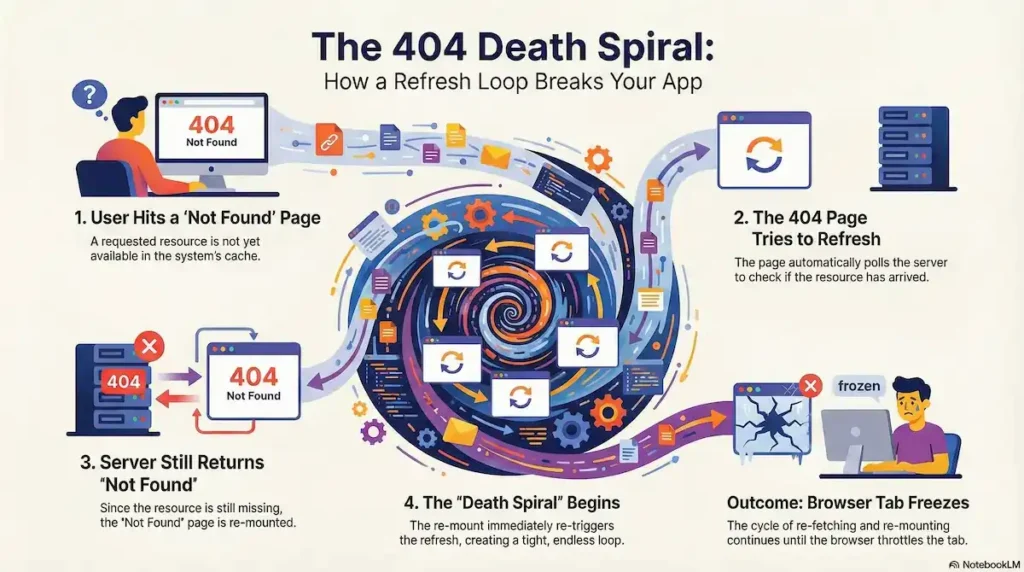

Escape From the Death Spiral: Fixing Infinite ‘router.refresh()’ Loops

Forensic Rule: Never place router.refresh() inside a raw useEffect (an effect without a specific, non-volatile dependency or an idempotency guard).

The Risk: When engineers are trapped by the “Black Box” of the 30-second cache, they often reach for a “manual override.” Without an Idempotency Guard (like a useRef flag to prevent recursive triggers), this creates a loop where the arrival of the new RSC payload re-triggers the effect, leading to an immediate Death Spiral.

In the Lab, we classify this recursive failure as the ‘Death Spiral.’ While technically an infinite loop caused by standard React lifecycle rules, the Next.js context makes it particularly lethal. Because router.refresh() preserves client-side state but requests a fresh server-side payload, it can silently satisfy its own dependency triggers. Without Idempotency Guards (like a ref-based ‘hasRefreshed’ flag), you are one render away from a Self-Inflicted DoS—spamming your own backend with RSC requests until the browser or the server gives up.

The Lifecycle Feedback Loop

The primary catalyst for this spiral is the fundamental mechanic of a Next.js refresh: it re-fetches the RSC payload from the server but preserves the client-side component state.

- The Trigger: A developer places

router.refresh()inside auseEffecthook to ensure data is fresh on mount. - The Execution: The refresh triggers a network request for a new RSC payload.

- The Conflict: Because

router.refresh()does not trigger a full page reload, the component tree remains mounted. If that component (or a parent) has a dependency—such as a data fetching hook likeuseSuspenseQuery—the arrival of the new RSC payload may trigger a re-render. - The Loop: This re-render re-executes the

useEffect, which callsrouter.refresh()again, creating a Self-Inflicted DoS (Denial of Service) attack against your own infrastructure.

Technical Definition: It’s a technical failure state where a frontend application unintentionally overwhelms its own server infrastructure with a massive volume of redundant requests. This is not caused by malicious external traffic, but by a logic flaw—typically a recursive loop—within the client-side code.

Forensic Marker: Unlike a standard infinite loop that freezes the browser main thread, a Next.js Self-Inflicted DoS is characterized by a “Heavy Loop.” Each iteration triggers a full network request for an RSC payload (React Server Component data). This consumes server CPU, database connections, and egress bandwidth simultaneously, effectively turning your legitimate user base into a distributed “botnet” attacking your own origin.

To prevent the “Death Spiral” (infinite router.refresh() loops), developers should implement a guard that ensures a refresh only occurs once per specific event, rather than re-triggering on every render cycle

import { useEffect, useRef } from 'react';

import { useRouter } from 'next/navigation';

export function ForensicDataSync({ status }: { status: string }) {

const router = useRouter();

// The Idempotency Guard: Prevents the "Death Spiral"

// We use a ref because changing it doesn't trigger a re-render.

const hasRefreshed = useRef(false);

useEffect(() => {

// Forensic Marker: Only trigger refresh if the data is "Stale"

// AND we haven't already performed a refresh in this mount cycle.

if (status === 'stale' && !hasRefreshed.current) {

console.log("Stale state detected. Executing guarded refresh.");

hasRefreshed.current = true; // Lock the guard

router.refresh();

}

}, [status, router]);

return <div>Status: {status}</div>;

}The 404 Death Spiral

A particularly destructive variant occurs within “Not Found” error boundaries. If a resource is not yet ready (e.g., a newly created record propagating through a database), developers may attempt to “poll” for its existence by calling router.refresh() from the 404 page.

- Step 1: The user hits a 404 segment because the record isn’t in the cache yet.

- Step 2: The 404 component mounts and calls

router.refresh()to check if the record has arrived. - Step 3: The router re-fetches, but if the server still returns a 404, the “Not Found” segment re-mounts.

- Step 4: This re-mount immediately re-triggers the refresh, locking the browser into a tight loop of re-fetching and re-mounting until the browser eventually throttles the tab.

Query Param Thrashing

This instability also extends to URL management. In scenarios involving authentication tokens or temporary state in search parameters, Query Param Thrashing can occur.

- Component A sees a

?token=...in the URL and callsrouter.push('/dashboard')to “clean up” the URL for the user. - Simultaneously, Component B or a server-side middleware detects the missing token and adds it back to ensure state persistence.

- The router is now caught in a perpetual state of URL reconciliation, re-fetching RSC payloads for every single change and locking the UI thread.

Understanding these failure modes is critical because the “Death Spiral” is rarely a bug in the code logic itself; it is a collision between the developer’s intent for freshness and the framework’s intent for state persistence.

Community Hacks: From Timestamp Injection to Middleware Vary Headers

The prevalence of “hacks” within the Next.js ecosystem serves as archaeological evidence of the framework’s initial architectural deficiencies. When documentation fails to provide a legitimate path toward data correctness, the community naturally gravitates toward subversion. These patterns—while often technically inefficient—were born out of a necessity to restore deterministic behavior to an otherwise unpredictable “Black Box.”

Community-Led Workaround: The “The Forced Entropy Pattern”

The most pervasive subversion identified in the community is the Timestamp Query Param Hack. Because the Client-Side Router Cache identifies route segments by their URL, developers realized they could force the router to treat every navigation as a “cache miss” by appending a unique string.

// The "Universal Bypass" pattern to force fresh data

const navigateToDashboard = () => {

router.push(`/dashboard?t=${Date.now()}`);

};While effective at ensuring the user sees the latest data, this creates a significant secondary issue: Cache Pollution. By appending a unique timestamp to every navigation, developers unwittingly flood the router’s memory with infinite variations of the identical RSC payload. In long-lived user sessions, this can lead to browser memory leaks as the heap is filled with redundant, timestamped versions of the same page segments that the router will never reuse.

Technical Definition: A state of memory inefficiency where the browser’s heap is flooded with redundant versions of identical route segments, caused by unique URL decorators (like timestamps or UUIDs) used to bypass framework caching.

Forensic Marker: This is identified by an ever-expanding memory footprint during a single user session. In the DevTools Memory Tab, search for multiple RSC Payload entries that are 99% identical but keyed to different query parameters. This restores Data Correctness but risks Session Instability on low-memory devices.

The Timestamp Query Param—or ‘Timestamp Injection’—serves as archaeological evidence of the community’s struggle with deterministic cache invalidation. By appending ?t=${Date.now()} to navigation requests, developers successfully force a Hard Cache Miss. While effective, our Lab identifies this as a ‘Debt Pattern’: it restores correctness at the cost of Cache Pollution, where the browser heap is forced to store redundant, timestamped segments of the same route.

The Middleware and “Vary” Header Failures

Advanced users attempted more sophisticated subversions by targeting the request-response lifecycle. A common “hack” involved using middleware.ts to inject specific headers, such as the Vary header or custom x-middleware-cache signals, to instruct the browser not to cache the resulting payload.

However, this approach frequently failed due to a fundamental architectural disconnect:

- Timing: The client-side decision to serve from the Router Cache happens before the request ever leaves the browser.

- Execution: Even if the request is sent, the generation of the RSC payload happens after the middleware has executed.

- Heuristic Dominance: The client-side router is programmed to prioritize its internal JavaScript heuristics (the 30s/5m timers) over standard HTTP caching contracts like

Vary.

The “Nuclear Option”: Why force-dynamic Failed

Many teams resorted to the “Nuclear Option”: setting export const dynamic = 'force-dynamic' globally across their application. This was a failed workaround because it addressed the wrong side of the equation. While it ensured the server (the supplier) was always ready to provide fresh data, it did nothing to change the behavior of the client-side router (the consumer). Even with a server set to dynamic rendering, the browser would still obey its hardcoded 30-second heuristic, serving a “ghost” state from memory and ignoring the fresh data available on the backend.

force-dynamic disables all caching.

Fact: It only affects the server-side; the client router still caches for 30s

These community-led patterns demonstrate a clear hierarchy of needs where correctness is prioritized over optimization. Engineers were willing to sacrifice performance, memory stability, and architectural purity just to ensure that when a user clicked a button, the data they saw was real.

The Version 14.2 & 15 Pivot: Reclaiming Control with ‘staleTimes’

The introduction of Next.js 14.2 and the subsequent shift in Next.js 15 represent more than just a feature update; they are an implicit admission of the architectural inadequacies of the early App Router era. By introducing the staleTimes configuration, the framework finally moved away from its “Black Box” philosophy, providing the “Admission by Configuration” that senior engineers had demanded for years.

Reclaiming Determinism with ‘staleTimes’

In Next.js 14.2, the framework introduced an experimental (now stable in v15) configuration object that allows developers to finally override the hardcoded 30-second and 5-minute buckets. This update provided the first legitimate “escape hatch” from the rigid caching heuristics that had previously forced developers into using timestamp hacks and manual refreshes.

// next.config.js (Next.js 14.2+)

const nextConfig = {

experimental: {

staleTimes: {

dynamic: 0, // Set to 0 to prioritize correctness over performance

static: 180, // Default reduced from 300s to 180s

},

},

};The “Dynamic: 0” milestone is particularly significant. By allowing developers to set the cache duration to zero, the framework acknowledged that for many real-time or transactional applications, the only acceptable client-side cache duration is none at all.

Solving Zeno’s Paradox: The Semantic Shift

Beyond simple timers, Next.js 14.2 addressed the core logic error that caused “Zeno’s Paradox.” The framework changed how it calculates staleness: it now tracks the time since the user navigated away from a page rather than the time since the initial fetch was performed.

This change effectively kills the “Reset on Navigation” bug. In the old system, checking for updates reset the timer; in the new system, frequent navigation within a session no longer keeps stale data alive indefinitely. This ensures that the “last active” timestamp doesn’t perpetually push the expiration boundary forward, allowing the cache to actually expire as intended.

The “staleTimes” Milestone (The Victory Lap)

The evolution of staleTimes is not just a feature update; it is an admission of architectural defeat by the framework. After nearly a year of “Black Box” behavior, Next.js has finally handed the “Keys of Truth” back to the developer.

- v13.4 – v14.1 (The Dark Era) The Client-Side Router Cache for dynamic RSC payloads was hardcoded at 30 seconds and completely opaque. This behavior was not configurable, forcing developers into “Forced Entropy” patterns (timestamp query-param hacks) just to ensure basic data correctness.

- **v14.2 (The Escape Hatch)**Vercel introduced the

staleTimesconfiguration. For the first time, developers could explicitly override the framework’s heuristics by settingdynamic: 0in thenext.config.js, effectively killing the 30-second “Ghost State” for dynamic segments. - v15.0+ (The Milestone of Correctness) Following the community’s forensic feedback, Next.js 15 changed the default behavior. The Client Router Cache now defaults

staleTimes.dynamicto 0 seconds. “Truth by Default” has finally replaced “Aggressive Caching.”

Next.js 15 completes this evolution by setting “uncached” as the default for page components. This move validates years of community resistance and “active subversion,” proving that while aggressive caching can improve synthetic benchmarks, it cannot come at the expense of application state integrity.

In the world of distributed systems, “Truth” must never be compromised for “Speed.” The recent updates to the Next.js Router Cache restore this balance, giving engineers the tools to ensure that what the server renders is exactly what the user sees—without the ghost of a 30-second-old payload haunting the UI.

Edge Case Q&A

router.refresh() is executed within a useEffect hook without strict guardrails. Since refreshes re-fetch RSC payloads but preserve client-side component state, the arrival of new data can re-trigger the render lifecycle, creating a recursive feedback loop that overwhelms the infrastructure and locks the UI thread. ?t=${Date.now()} forces a cache miss, it triggers progressive “Cache Pollution”. Every navigation floods the router’s memory with an infinite variation of identical RSC payloads. In long-lived sessions, this leads to significant memory leaks as the browser heap swells with redundant, timestamped versions of pages the router will never reuse. Related Citations & References

- NEGuides: Caching | Next.js

- GIDeep Dive: Caching and Revalidating · vercel next.js · Discussion #54075 · GitHub

- GIISR revalidation is using stale data · Issue #58909 · vercel/next.js · GitHub

- GIrevalidatePath doesn't clear cache for client-side navigation · Issue #61184 · vercel/next.js · GitHub

- NEGuides: Prefetching | Next.js

- GIrevalidation is not triggered by “ with app router · Issue #50362 · vercel/next.js · GitHub

- GIrevalidatePath() not working as expected for Parallel Routes, or for Parallel + Intercepting Routes (modal) · Issue #54173 · vercel/next.js · GitHub

- GIuseSuspenseQuery infinite refetch after SSR (Next.js App Router) · Issue #6116 · TanStack/query · GitHub

- GIRouter.replace in useEffect creates infinite loop · vercel next.js · Discussion #46616 · GitHub

- STNext.js not-found infinite reload loop – Stack Overflow

- GInot-found.tsx: Infinite Loop when a Component Calls router.refresh · Issue #86197 · vercel/next.js · GitHub

- STreactjs – Updating state on Next.js router query change causes infinite loop – Stack Overflow

- STreactjs – How do I add a query param to Router.push in NextJS? – Stack Overflow

- GICache HITs with query parameters? · vercel next.js · Discussion #12736 · GitHub

- GINext.js and Vary — why it’s currently impossible to cache variants “properly” · vercel next.js · Discussion #82571 · GitHub

- GIApp Router Custom Header Use Cases · vercel next.js · Discussion #58110 · GitHub

- NEnext.config.js: staleTimes | Next.js

- NENext.js 14.2 | Next.js

- NENext.js 15 | Next.js